Novice investors are often warned against backing a company just because they appreciate its products. Loving your iPhone? It does not automatically follow that you need Apple (US:AAPL) in your portfolio.

Yet buying shares in a company you know well holds undeniable appeal – even for seasoned stockpickers. You understand its products and the investment case, so you wish to partake in its growth story. While you still need to dot your ‘I’s and cross your ‘T’s on the financials, this can be one of the pleasures of investing in the stock market; not even fund managers are completely immune, as our Shares I Love column sometimes demonstrates.

Traditionally, for private investors, taking a stake in a business like this was only possible if it was listed on the stock market. In recent years that has changed, to an extent. Private investors can acquire exposure to private equity via investment trusts; although these tend to be picked based on their overall approach – the lifecycle stage and sectors of the companies they own, their record on performance and realisations, and so on.

Transparency is not this industry’s strongest suit, so it can be hard to learn much about these trusts’ individual holdings – particularly compared with the levels of disclosure on offer in listed markets. But if you look under the bonnet, you can still find the basics – such as the private companies they invest in and the levels of exposure they have – and more significant detail such as how the investment appears to be performing.

IPO candidates and fintech

The majority of private companies in trust portfolios are names that only experts in certain sectors will be familiar with. But the table below lists 11 private companies that UK investors may recognise.

| Company | Company sector | Trust | AIC sector | Private company portfolio exposure (%) | As at |

| Action | Consumer | 3i Group | Private equity | 63.5 | December 2024 |

| NB Private Equity Partners | Private equity | 5.9 | February 2025 | ||

| Patria Private Equity | Private equity | 2.4 | September 2024 | ||

| Pantheon International | Private equity | 1.2 | February 2025 | ||

| HarbourVest Global Private Equity | Private equity | 0.7 | July 2024 | ||

| Klarna | Fintech | Chrysalis Investments | Growth capital | 15 | December 2024 |

| Revolut | Fintech | Molten Ventures | Growth capital | 9.2 | September 2024 |

| Schroders Capital Global Innovation Trust | Growth capital | 9 | December 2024 | ||

| Starling | Fintech | Chrysalis Investments | Growth capital | 29 | December 2024 |

| SpaceX | Space | Edinburgh Worldwide | Global Smaller Companies | 13.6 | February 2025 |

| Baillie Gifford US Growth | North America | 11.1 | February 2025 | ||

| Schiehallion Fund | Growth capital | 9.5 | February 2025 | ||

| Scottish Mortgage | Global | 7.2 | February 2025 | ||

| RIT Capital | Flexible investment | 0.7 | December 2024 | ||

| Shein | Retail | HarbourVest Global Private Equity | Private equity | 2.2 | July 2024 |

| Freetrade | Fintech | Molten Ventures | Growth capital | 1.3 | September 2024 |

| North Sails | Retail | Oakley Capital | Private equity | 16.2 | December 2024 |

| Dexters | Property services | Oakley Capital | Private equity | 3.5 | December 2024 |

| Tide | Fintech | Augmentum Fintech | Financials & Financial Innovation | 21.7 | September 2024 |

| Zopa | Fintech | Augmentum Fintech | Financials & Financial Innovation | 14.3 | September 2024 |

Even this list is a broad collection, ranging from star companies almost everyone will know to more niche choices. The companies are at different stages of their lifecycle, as partly reflected by the differences between the investment trusts that own them. Private equity trusts tend to invest in more mature and cash-generative companies (relatively speaking), while on the ‘growth capital’ side you will find racier options.

Many of these companies operate in the financial technology sector. The UK is brimming with fintech companies, but not all of them go public and many tend to stay private for longer than they once did. Investment trusts can be a way to gain exposure to a domestic sector that has shown the capacity for innovation and growth over the years.

Some of these trusts are fairly concentrated, with significant weightings in their top holdings – often upwards of 20 per cent – meaning the fate of individual companies has a big impact on their performance. And a fast-growing company can quite easily become an oversized portion of the portfolio: trimming an unlisted position is not as easy as with listed companies.

Conversely, other trusts – particularly funds of funds such as HarbourVest Private Equity (HVPE) – hold myriad businesses and make diversification one of their key selling points, so a single company won’t have much of an impact on their net asset value (NAV), even if it does very badly or very poorly.

The UK is brimming with fintech companies, but not all of them go public and many tend to stay private for longer than they once did

Growth capital trust Chrysalis Investments (CHRY) falls into the first category. Its two biggest holdings, Starling Bank and Klarna, are recognisable brands often featured in the press, and together account for 44 per cent of its assets.

Since its foundation in 2005, Swedish fintech Klarna has become synonymous with buy-now-pay-later services, which are offered at the checkout by a number of major brands across a range of sectors, including the likes of Apple, Shein and Airbnb. After years of speculation, the company is now on the verge of going public, having filed initial public offering documents in March. It is reportedly targeting a valuation of $15bn (£11.6bn) – albeit last week’s market sell-off has seen it “pause” its plans for now.

When the listing happens, investors will find out how the market price compares with Chrysalis’s valuation of its stake in the company. Numis analysts estimate that the trust’s September 2024 NAV is based on a valuation of roughly $14.6bn for Klarna. At that time, the stake was valued at £120.6mn, while the cost stood at £71.5mn – a total return of about 69 per cent. In December 2024, Chrysalis further increased its valuation of Klarna to £143.6mn, of which £8.2mn came from a new secondary investment. The trust first invested in the company in August 2019 but has topped up its position multiple times since.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

It’s worth keeping in mind that even if Klarna’s IPO goes as planned, this will not necessarily result in instant liquidity for the trust. Often, existing investors in a company are not allowed to sell their stake for six months or a year, notes James Carthew, head of investment companies at QuotedData. So the final exit can depend on what happens to the share price in the interim.

Occasionally, trusts hold on for longer periods to former private holdings that have undergone an IPO. Private equity trust Oakley Capital (OCI) still has an investment in Time Out Group (TMO), which listed in 2016 – as at December 2024, the stake, split between equity and debt, was worth £77mn.

The other high-profile Chrysalis holding, Starling Bank, is a so-called challenger bank, launched with the intent of providing better digital services and lower fees to customers.

You may be just as – or even more – familiar with Starling’s competitor Monzo. Founded in 2015 by Tom Blomfield, the former business partner of Starling founder Anne Boden, after the two had a falling out, Monzo’s is a story that has produced plenty of media interest over the years. Despite the similarity of their business models, Starling became profitable two years earlier than Monzo.

In the year to March 2024, the bank’s pre-tax profit grew 54.7 per cent to £301mn. There is also a lot of excitement around Starling’s subsidiary, Engine, which is the bank’s way of expanding internationally – selling its banking software, rather than its banking products.

Despite the similarity of their business models, Starling became profitable two years earlier than Monzo

The bank is a potential IPO candidate, but the timeline remains a big question mark – as do other aspects of the company. Last year, the Financial Conduct Authority fined Starling £29mn for what it described as “shockingly lax” screening controls that left the financial system “wide open to criminals and those subject to sanctions”.

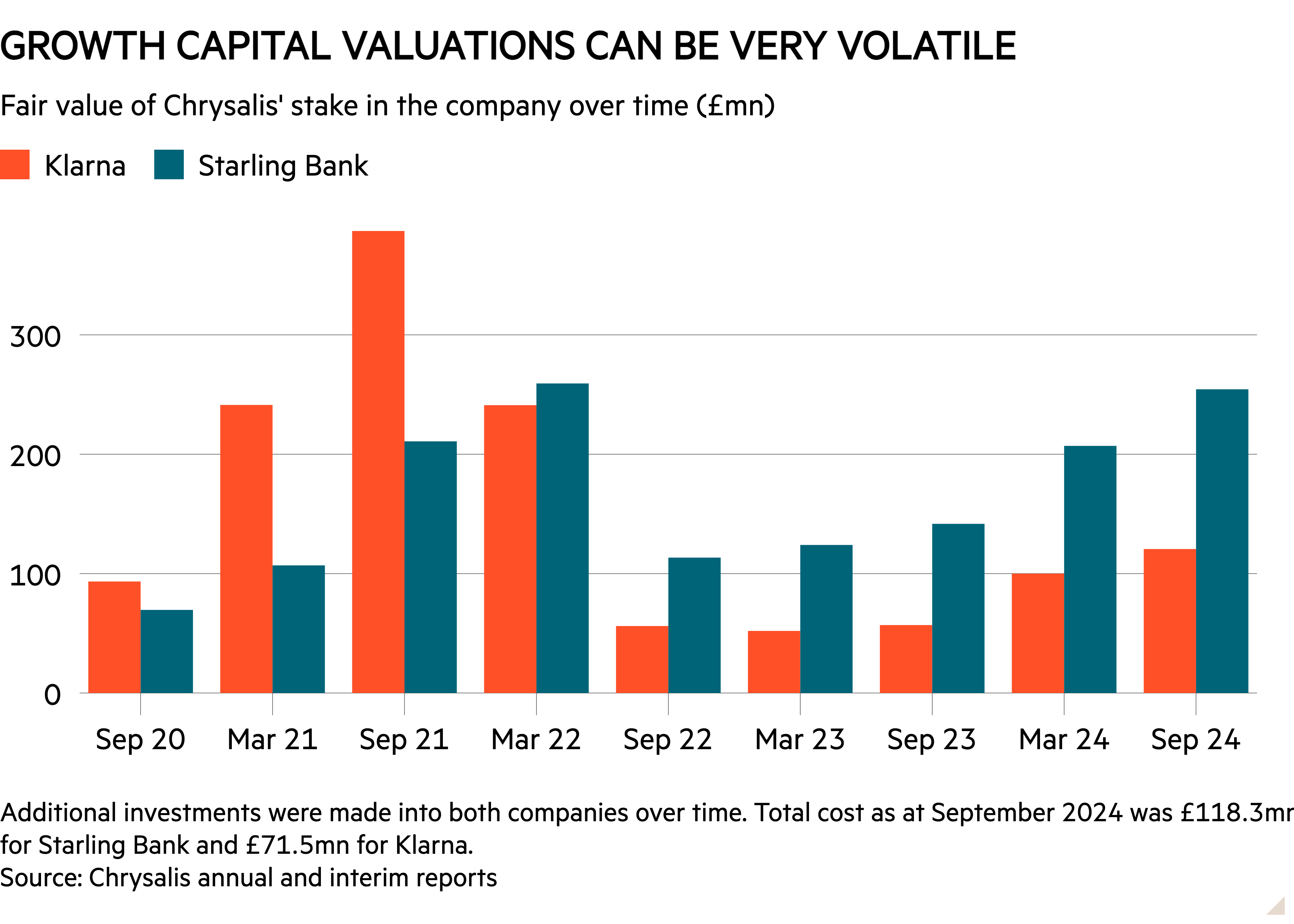

Klarna and, to a lesser extent, Starling show how investing in high-profile companies can lead to volatile valuations– particularly when the market turns like it did in 2022. At its peak in 2021, Klarna was valued at $45bn, only for this figure to come crashing down to $6.7bn the following year.

“You had all of the excitement in the easy money times, when the way people pay for stuff was changing, and Klarna was just doing really, really well. But it was sucking in loads of capital to maintain that growth, and in the excitement, the valuation reached silly levels,” explains Carthew. In 2022, when interest rates went up, Klarna still needed capital to expand and had to raise money in a much more challenging environment, a process that led to the valuation drop.

This episode is instructive. Private valuations are often “smoother” than those in public markets, because they do not change on a day-by-day or even week-by-week basis. This is arguably one reason why institutional investors have increased their exposure to the sector in recent years.

But if a company needs to raise capital the price at which lenders are prepared to provide money can sometimes mean harsh realities.

Since that time, however, Klarna has become profitable, partly by reducing its workforce and automating some of its processes via artificial intelligence; this means it is now in much better shape for an IPO, Carthew argues.

In the year to September 2022, Chrysalis’ stakes in Klarna and Starling were marked down by 87 per cent (from £387mn to £49mn) and 51 per cent (from £211mn to £103mn), respectively. Conversely, in the year to September 2024, valuations rose by 111.8 per cent for Klarna and 79.5 per cent for Starling.

Another widely known fintech company that is similar to Starling Bank is Revolut, which is held by growth capital trusts Molten Ventures (GROW) and Schroders Capital Global Innovation Trust (INOV) – the portfolio previously known as Neil Woodford’s Patient Capital trust, which is now in the process of winding down.

Revolut also launched with the purpose of disrupting traditional banking, by offering a digital-only card that allows customers to hold money and make payments in different currencies for free or at very low fees. A number of features have been added since, including stock and crypto trading.

For a long time, however, the company did not have a banking licence in the UK. This was a major barrier to profit generation because, without it, the company could not offer any kind of lending products. The licence was belatedly secured in July 2024 and Revolut is now in the process of building its banking operations.

Both Molten Ventures and Schroders Capital Global Innovation Trust subsequently boosted the valuation of their Revolut stakes – the former increased its by 90 per cent in its report for the six months to September 2024, and the latter by 85 per cent in the year to December 2024. This was also partly to account for a secondary share sale that valued the company at $45bn, and was reportedly worth up to $500mn.

Revolut has had an impressive growth trajectory. In 2023, it made $2.2bn in revenue and $545mn in pre-tax profit. In the first half of the following year, it said it saw an annual increase in revenue of more than 80 per cent. Still, $45bn looks like a potentially ambitious valuation, when you think that Barclays has a market cap of about £42.5bn. This week the company was fined €3.5mn (£3bn) by Lithuanian regulators over money laundering failures

Baillie Gifford in space, and others

One of the hottest private companies in the world is SpaceX. Investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford are the main option for private investors wishing to access Elon Musk’s space venture, with Edinburgh Worldwide (EWI) having the biggest exposure as a percentage of total portfolio assets.

Not a lot is public about SpaceX’s performance, but it is huge in its field. “In 2024 alone, it conducted 134 orbital launches, which represented more than half of the global total,” explains Mick Gilligan, head of managed portfolios at Killik & Co. “To put that into context, the firm’s 2024 global payload mass (successful launches into low Earth orbit) was 20 times bigger than the number-two player, CASC, China’s state-owned aerospace company.”

The company is estimated to have generated $13bn in revenues last year, and in December reports of a tender offer allowing staff to sell some shares suggested a valuation of up to $350bn – higher than that of Coca-Cola (US:KO), notes Gilligan.

Investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford are the main option for private investors wishing to access Elon Musk’s space venture

A month earlier, there were also reports of a separate tender offer for existing investors, which valued the company at around $250bn. Numis analysts said that, judging by the changes to portfolio exposure, Edinburgh Worldwide and Schiehallion (MNTN) appeared to have used the tender to trim their positions in SpaceX. But the higher valuation that the company attracted the following month drove exposure levels up again.

Scottish Mortgage (SMT) put the company’s total return in the last quarter of 2024 at 77 per cent, and the value of the trust’s stake in SpaceX rose from £624mn in September 2024 to £1.1bn in February this year.

The trust values companies on a three-month rolling basis, meaning a third of its private portfolio is valued each month. Changes to the valuations of comparable listed companies can trigger adjustments, so the trust’s SpaceX valuation is likely to continue to fluctuate over time – particularly if the stock market retreat of the past few weeks continues, and perhaps also depending on what role Musk continues to play in US politics.

The other companies listed in the table are less well known, but many are still of interest. European discount retailer Action isn’t an especially well-known brand in the UK. However, it deserves a place in the list because of the unique prominence it has in the private equity trust landscape.

The Dutch discount retailer represents a giant portion of the portfolio of the UK’s largest investment trust, 3i Group (III). As a result, investors often now see 3i as simply a proxy for gaining exposure to Action, and because 3i is a FTSE 100 company, it is also found in a number of trusts that invest only in listed companies.

Action is performing well, and in 2024 grew net sales and operating Ebitda by 22 per cent and 29 per cent, respectively. However, 3i’s popularity means it was trading at a hefty premium of 52.2 per cent as at 3 April. In February, Numis analysts downgraded the trust from buy to hold “on the back of strong recent share price performance”, arguing that while Action is expected to continue to perform strongly, “the general economic, geopolitical and political backdrop results in challenging conditions across much of the portfolio”.

Various other private equity trusts hold smaller stakes in Action. This is not entirely unusual – another reason looking under the bonnet is interesting is because it also gives a flavour of the connections between different private equity managers. There is a degree of overlap between the portfolios of different private equity trusts, although it is quite low.

Norwegian software company Visma, for example, is a holding of at least four different private equity trusts. They include principal owner HgCapital Trust (HGT) and three more diversified trusts that invest partly as funds of funds, and which invested in the company through or alongside HgCapital – Patria Private Equity (PPET), Pantheon International (PIN) and ICG Enterprise Trust (ICGT).

The valuation problem

Companies such as SpaceX and Klarna show how complicated valuing a private company can be – particularly when they become very big and well known.

Part of this is just the nature of private markets. As Joseph Rowland, funds research analyst at Rathbones Investment Management, puts it: “Something is only worth what someone else is willing to pay for it, meaning that until a position is sold, the accuracy of the valuation is unavoidably uncertain.”

Early-stage growth companies are especially tricky because they do not typically generate any cash, and need to raise money to support their growth instead.

“Funding rounds can often trigger revaluations, and rightly so – they indicate what another investor was willing to pay for shares in the company,” says Rowland. “However, investors should ensure that valuation adjustments reflect the size of the funding round.” During a funding round, investors might be willing to pay a certain figure for a stake in a company – but if the stake is relatively small, that does not necessarily reflect the figure the market is willing to pay for the company as a whole.

Discounts make the sector more attractive, at a time when geopolitical uncertainty has once again made the outlook for growth companies look more difficult

There is also a difference between taking part in a funding round and trying to sell an existing stake, notes Charles Murphy, senior research analyst at Singer Capital Markets. A manager may find themselves in the uncomfortable position of wanting to sell an existing stake due to valuation concerns but being unable to do so, at the same time as a fresh funding round for the same company takes place. That funding round has to be recognised as part of the valuation and pushes it up further.

Because there isn’t much information on private companies available, it can be hard to form an independent opinion on the value of the business. Investors often have to look at the long-term track record of the fund manager instead. UK companies have to file accounts, and they can be useful to look at – they are not very up-to-date but you can at least get a feel for the company’s progression. But this does not apply in all jurisdictions.

The Financial Conduct Authority recently carried out a review into the valuation processes of private market assets, and said firms need to make improvements – especially in identifying “potential conflicts of interest in the valuation process” and ensuring they are independent.

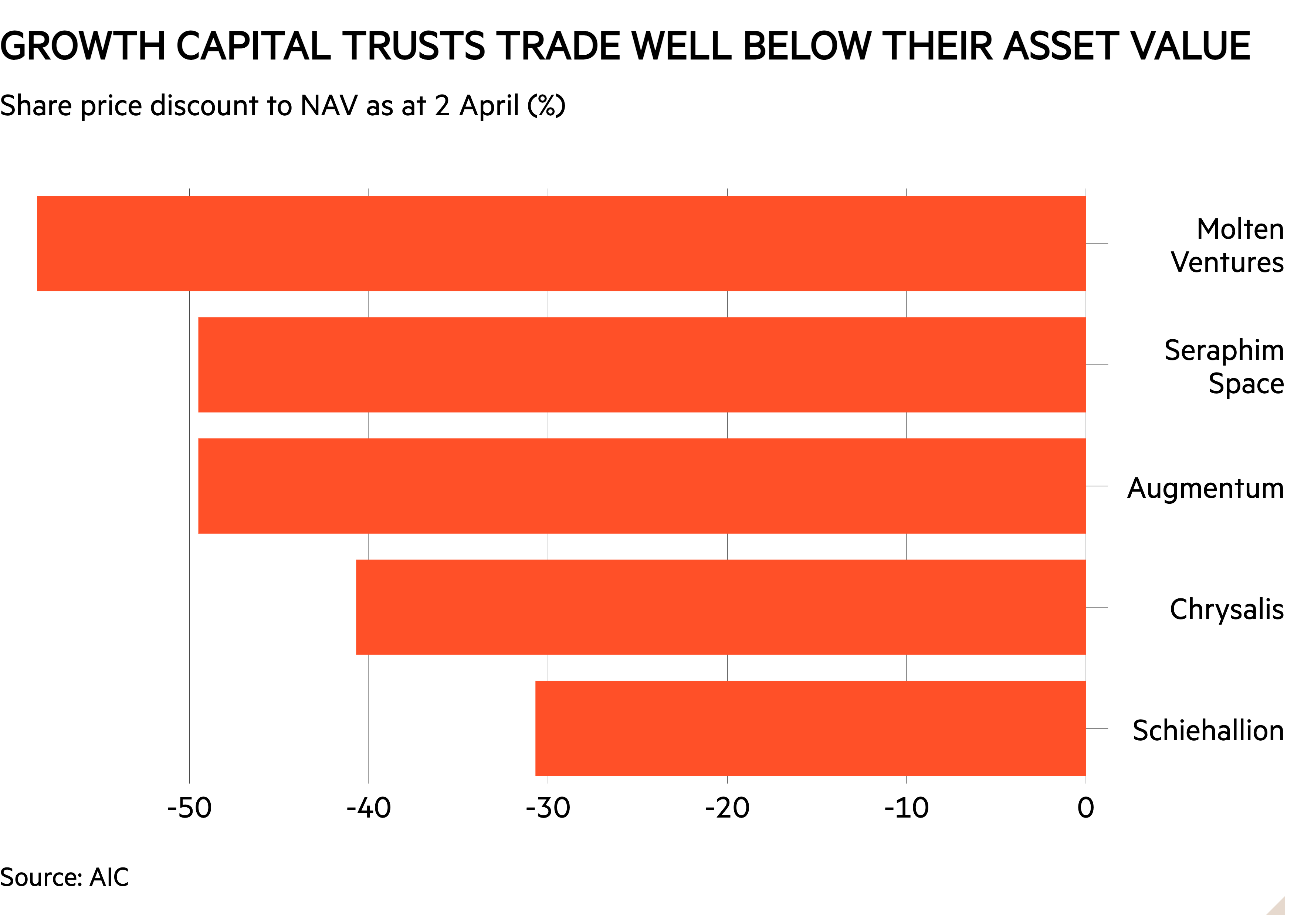

Investors’ valuation scepticism is one reason growth capital trusts trade at significant discounts to NAV, as the chart below shows.

Gilligan argues that both Molten Ventures and Augmentum Fintech (AUGM) look cheap, given their strong track records. On Molten Ventures, he says: “Portfolio companies that are raising capital are doing so at or above holding values. The portfolio is diversified, with more than 100 holdings. About 60 per cent of the NAV is forecast to grow revenues at 48 per cent during 2025. I am a holder, personally.”

Discounts make the sector more attractive, at a time when geopolitical uncertainty has once again made the outlook for growth companies look more difficult. Growth capital trusts make exciting private companies accessible to private investors – but if you invest, you must be prepared to withstand the sector’s volatility, including that which comes with valuation shifts.