SolStock

The Little Book Of Value Investing

One of the best books in the “Little Book” value investing franchise is Christopher Browne’s The Little Book of Value Investing. It is one of the few in the little book series that was written by an actual renowned fund manager. The others would be the books by Joel Greenblatt and John Bogle.

Christopher Browne of Tweedy Browne Company LLC was a well-known value investor from the Benjamin Graham school of thought. Low P/E ratios, low book values, and strong balance sheets. Not a believer in fixed-income assets like bonds; he believed the majority of a person’s funds, even into retirement, should be kept in equities. The risk of losing time in the market was far too great to be tied up in fixed-income assets that are also subject to the whims of the bond market.

In his only book, he provides some logical advice that I have also taken as my primary method of portfolio allocation that I will adhere to, one day when I am fully retired.

A few different scenarios

The basic premise of Christopher Browne’s book is to be in equities, and cheaply priced ones to boot. There are several index funds and proxies we can look at later to fit the bill. The other recommendation he had is to leave at least 3 years’ worth of living expenses in non-volatile cash equivalents. That would be your money markets, short-term bond funds, and liquid CD accounts. Allow compounding to work for as long as possible by not touching your stocks.

He still advised his clients to use the 4% rule but to feed from the cash equivalent account when the market is having a down year. Long-duration bonds were never part of the equation for his multi-millionaire clients going through retirement.

Even better yet, if the portfolio is sufficiently large, his clients could use cash accounts exclusively for their living expenses rather than touching equities at all. Many of his clients retired with ample amounts of Berkshire Hathaway holdings. He recommended not touching that holding for as long as possible and just making sure that a few years or more was in cash equivalents and just forget about your equities.

In his case studies, all his clients both had funds to live on and grew their nest eggs. When compared to some of his clients that refused to hold anything but bonds into retirement, the divergence in wealth accumulation was stark.

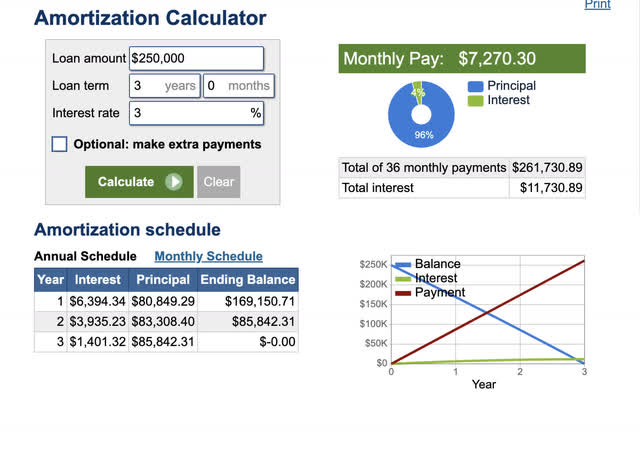

Amortization of $250,000 in a hypothetical $1 million retirement portfolio

A first example we can use here for the bold that wish to both A. make the most out of stock market compounding and B. have no other supplemental forms of income like rental properties or social security, we can see what would happen if we were to exclusively draw on a money market account for living expenses while leaving our diversified stocks alone and assuming they can match the long term total return average of the S&P 500.

Using a basic amortization calculator on a mortgage, we can assume that the numbers would work out the same as if we were a bank collecting on a 3-year note. I am assuming that long-term money market rates settle at 2-3%.Here, $250,000 would allow you to draw a little more than $80,000 a year while collecting $11,730 during this time frame.

Now let’s see what happened to our stocks over a few different compounding scenarios.

This will be an all-equities portfolio with an average dividend yield of 3% reinvested.

3 years of compounding scenarios

$750,000 at a 3%[equivalent to $1875/mo] dividend yield with principal growing at an average of:

- 9% 3 years compounding plus average of $1875 reinvestment per month=

$1,045,029.00

- 8 % 3 years compounding plus average of $1875 reinvestment per month=

- $1,017,828.00

- 7% 3 years compounding plus average of $1875 reinvestment per month=

$991,117.50

7% is thus the break-even point considering an additional $11,730 drawn off of the $250k money market portion in hypothetical interest.

The idea in the aggressive investor portfolio is to sell off $250k in stocks after all funds have been drawn off the money market account and then reinvest that amount back into the cash account for another 3 years’ worth of living expenses. Since we also collect around $10,000 in interest over that period from the cash account, that amount should be reinvested periodically back into the stock portfolio.

This would create a break-even scenario at a 7% average appreciation over a 3-year period where your pie would return to $1 million if you had a stock portfolio with an average 3% dividend yield.

About taxes

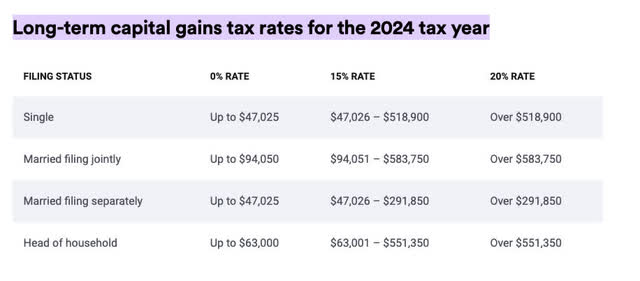

While everyone’s tax situation is different, the below scenario uses a liquidation of at least $250,000 in stocks every 5 years. The modeled amounts are not adjusted for taxes and are just hypothetical. However, as it stands in 2024, up to $94,050 for married filing jointly in the US are in the 0% tax bracket for long term capital gains.

If you are living solely on stocks, cash equivalent drawdowns and social security, there is a good chance that much of this maneuvering will be tax free, especially when selling only your shares with the highest cost basis every 5 years.

5 years is more realistic and let’s forget about trying to get a 3% yield

If you are of normal retirement age, there is a good chance that you have social security payments and possibly a rental property to boot. Drawing down the $250k cash equivalent portion over 5 years would allow a $50,000 draw per year and provide a bit more interest income over the longer amortization. The goal here is to see how an all-equity portfolio of the broader market held up in even the worst 5-year periods in recent memory.

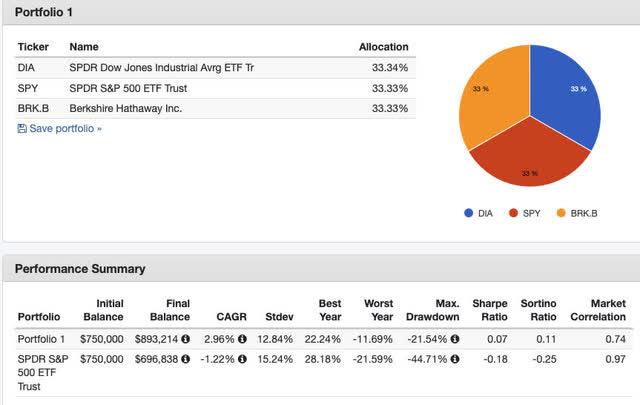

For this purpose, we are going to use older established ETFs and broad market proxies for the backtest. All dividends must be reinvested, not used for living expenses. Our model portfolio will contain the following:

- Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.B)(BRK.A)

- SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY)

- SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average ETF Trust (DIA)

- The final portion, $250k is held in cash equivalents and drawn down over 5 year periods.

Note, the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust tends to outperform in good years due to a higher proportion of growth stocks. Both the SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average ETF Trust and Berkshire Hathaway tend to outperform in bad years for the market.

2000-2005

With this now 5-year amortization of $250,000 at an average 3% interest rate, we would collect $19,530 over this period in interest. Assuming taxes are paid by a retiree in the 20% tax bracket, would leave us with a remainder of $15,624. Adding this back to the $893,214 during this dreaded period leaves us with $908,838. Let’s deduct $250k from this and start the next period with $658,838 in the equity portion.

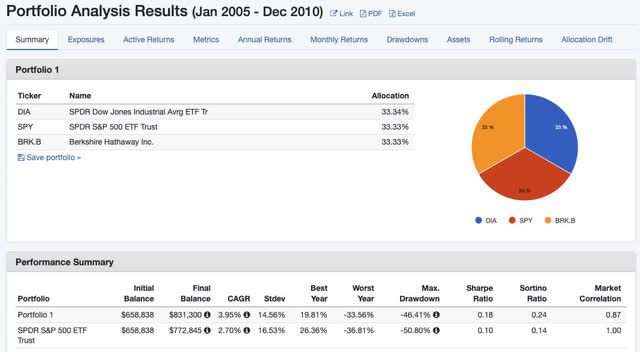

2005-2010

Again, another terrible period for the market where we only realized a 3.95% CAGR. Adding back our $15k in interest to the pile leaves us with $846,300. Deducting $250,000 once again leaves us with $596,300. This period was a historical anomaly and extremely rough. Let’s see what happens in the next period.

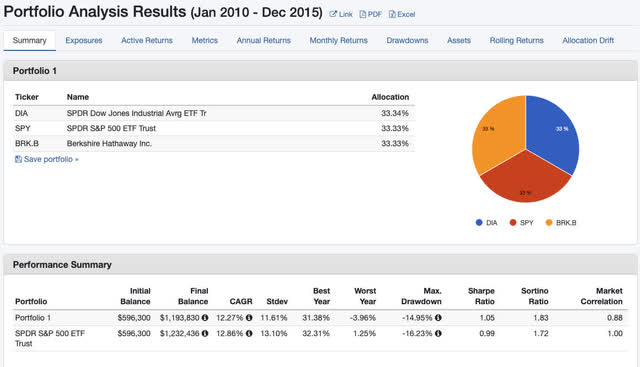

2010-2015

Now we’re cooking. The portfolio is now worth nearly $1.2 million plus the interest collected along the way from our cash equivalents. Letting the market do its work for you, and reinvesting your dividends, which are qualified and probably tax-free if your household income does not exceed $100,000 total income, has worked in your favor through even the absolute worst of times. Those dividends have bought you more shares at the bottom rather than buying you more oats at the grocery store.

The advice of Christoper Browne that he gave to all his clients at Tweedy Browne works. Keep your living expenses in cash equivalents, not bonds which are also subject to market fluctuations, and let the market work for you.

Let’s take a look at what happens in this most recent 5 year period under this same strategy:

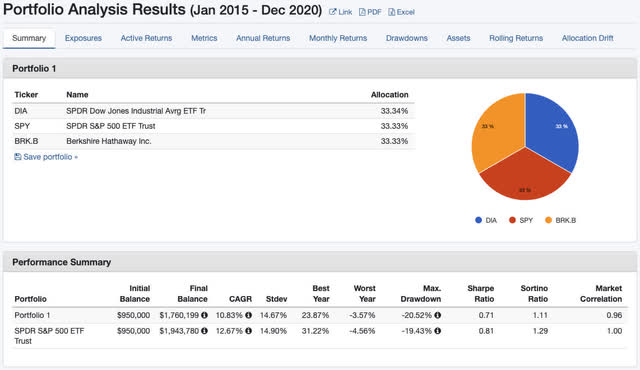

2015-2020

Even better, we now have a $1.76 million nest egg 20 years into retirement living on this strategy. While adding Berkshire Hathaway and The Dow Jones Index fund lagged the market in the bull years, it beat the market in the bear years. Berkshire, as Warren Buffet has stated, is designed at this point to perform as so. The Dow also tends to outperform the S&P 500 in bear years as well.

Good alternatives to money markets

One more book from the Little Book series by Wall St. Journal columnist and Intelligent Investor editor Jason Zweig is The Little Book of Safe Money. This book was written just after the great financial crisis when even some money market funds became frozen when The Reserve Primary Fund “broke the buck” due to commercial paper in the fund issued by Lehman in 2008 going bad. While investors were finally made whole, some were locked out of withdrawals for weeks to months.

Also, certain cash equivalent funds fall under SIPC rather than FDIC, which as Zweig noted, made some of the fund liquidity process a bit more lengthy than it would have been under FDIC. He advises being only in the most liquid of money market funds that deal in U.S. government federal debt rather than those that contain commercial paper to juice a tad more yield. Always expect the unexpected.

Even better now, a few institutions offer fully liquid deposits that are FDIC-insured and yield only 10-20 basis points less than money market funds.

Bank of America through Merril Lynch has a preferred deposit program that is same-day liquid during trading hours any business day Monday through Friday. FDIC insured up to $250,000 per account.

Vanguard has a similar product that they just launched. These usually have minimum deposit requirements of around USD 100,000.

Don’t reach for yield

Many retiree fund setups are aligned with reaching for yield. Some of the recent high-yield leveraged option funds are not new and were around even in the 80s and 90s. Here is another summary parable from Jason Zweig’s book:

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as interest rates came down, bond yields fell sharply, so called option income or government-plus funds had gathered billions of dollars from tens of thousands of investors-many of them retired or elderly, who simply wanted a stable stream of ample income to supplement their pensions or Social Security.

The government-plus funds used a strategy that managed to be both incomprehensible and stupid at the same time. They sold away the right to keep their long term bonds, in exchange the funds got a short-term gusher of cash using call options.

But the yields were bogus. As interest rates continued dropping, the funds had to sell all their best long-term bonds below fair-market value; the extra income disappeared, they took a loss on the bonds, and they could replace them only with more expensive bonds that offered less income.

Investors in these Frankenstein funds found that their yield kept dropping and the value of their accounts kept shrinking. Month after month they took another battering.– Jason Zweig The Little Book of Safe Money pp.60-61

I’m not sure what negative catalyst could screw up J.P. Morgan’s ultra-popular covered call funds (JEPI) and (JEPQ), but as Zweig noted, when you reach for yield in creative manners, it sometimes comes back to bite you when you least expect it.

Being both liquid and solid

One more premise I like from Zweig’s book is the notion that your portfolio has to be both liquid and solid. Of course, the liquid refers to “liquidity”. Always ask yourself how liquid are your assets that you plan to live on for the next 3 to 5 years. Giving up larger growth rates for increased liquidity, at least for the fixed income part of your portfolio can prevent dumb mistakes, The compounding and dividend reinvestment into the broader market is one is the most important aspects of this portfolio strategy. Having fully liquid, non-fluctuating living expenses is a psychological advantage.

Risks

This is for the most part, an all-equities portfolio. It will have volatility in excess of a 60/40 or 50/50 bond to equity allocation. This is set up for the investor that would like to both maintain their lifestyle and grow their nest egg on the basis that they believe the market will over longer periods, return what it normally has and be efficient.

Furthermore, Berkshire Hathaway 5-10 years from now could have different leadership and decision-making qualities than it does today. I believe the company at this point is on autoplay. Next man up, most like Gregory Abel will be tasked to maintain Berkshire’s private operating standards combined with prudent portfolio management. This is my personal assumption that he can maintain Buffett’s standard. As Berkshire is part of this portfolio as a hedge against bear markets, for which it is set up to perform better than the S&P 500, it may lose that quality.

The Dow 30 is also included to perform this loss dampening in bad times but could be less efficient than it has been historically with it’s now larger segmentation of “Big Tech” versus true industrials.

Summary

In summation, this is how a model portfolio would look along this backtest model, this uses the iShares 0-3 Month Treasury Bond ETF (SGOV) as the cash proxy, but U.S. government money market funds or FDIC insured deposit accounts all fit the bill:

- Feed on the cash equivalent portion, FDIC-insured deposits could be an even better alternative to money markets and short-term Treasuries.

- Replenish cash equivalencies every 5 years to meet the next 5 years of living expenses.

- Reinvest all dividends into the 3 broader market index funds and proxy.

- Let compounding do its work. Don’t forget, the very dividends you are living off of in some retirement models are the very dividends that can buy you cheaper shares if a bear market hits.