By Brittany Jesslop, TheDollarHub.com — Filed June 2020, Chicago

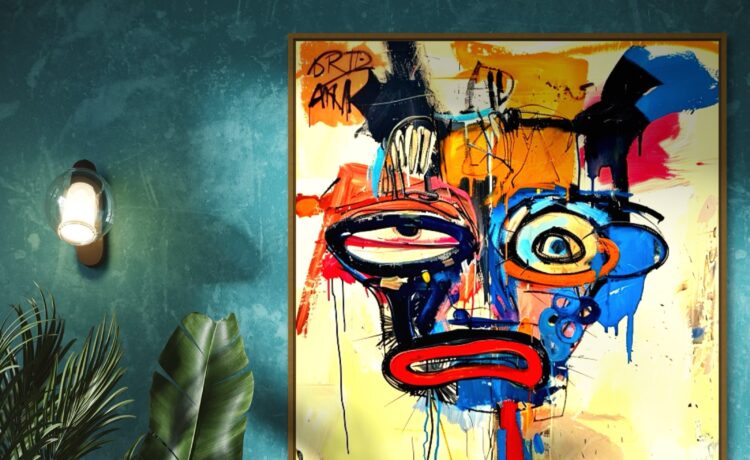

The sound comes first—the staple gun’s bark, rapid and nervous, as crews throw up plywood like shields. Then the color: fresh murals rising overnight, grief and the demand for change painted in quick strokes across a city suddenly speaking in boards. In the weeks after the police killing of George Floyd, Chicago’s storefronts become impromptu canvases while streets fill with voices and cameras and sirens. Artists move fast, because the moment is moving faster. What gets painted in haste may be remembered in history—and no one is quite sure who will keep it safe or for how long.

Against that fevered backdrop, Pierre Simone makes a decision that doesn’t look like a headline but feels like a pivot: pull the work. Cancel the release. Remove the canvases from the circuit of previews, dinners, and back-room whispers that push art toward transaction. Withdraw, for now, and let the streets—not a salesroom—carry the message. He and his estate suspend a Chicago unveiling that had been months in the making, choosing silence over spectacle, time over timeliness.

“Not like this, not now”

What I can report, on background from people familiar with the talks, is straightforward. In late June, Simone’s side told the host gallery they would pause any unveiling of the 2018–2020 canvases, a mature, tightly curated body of work slated for a quiet summer release. The reasoning wasn’t marketing calculus—it was ethics and optics in a city at full throttle. To proceed, they felt, would turn the artist’s name into the wrong kind of signal: merchandise in a moment that demanded mourning and structural change. The estate’s phrasing to me was clear enough to be quotable without quotation: place with love, or not at all.

Inside the gallery, the decision landed hard. Contracts have calendars; payrolls have realities. But the counter-argument—visibility helps the cause—collapsed under the weight of context. Visibility can be a virtue; it can also be a siphon, drawing energy away from the street into the safety of culture-talk. Simone chose the street.

Chicago redraws its symbols—in paint and in bronze

If you want the city’s mood in a single image, you can take your pick. A hand reaches across fresh grain to finish a mural that didn’t exist at sunrise. A circle of volunteers catalogues plywood sheets before they’re hauled to storage, trying to keep the art from the landfill of busy news cycles. A young conservator photographs bracing patterns, already thinking months ahead about preservation, even as collective attention is still on the march. By mid-July, “what do we save?” becomes a civic question, not a curatorial niche, and artists, organizers, and the city begin to formalize ways to keep the boards—and the voices on them—from disappearing.

At the monumental scale, Chicago redraws its stance just as quickly. On July 24, 2020, city crews remove the Christopher Columbus statues from Grant Park and Arrigo Park, officially labeling the move “temporary” while acknowledging the escalating public safety concerns and the need for a deeper reckoning with what belongs on a pedestal. The absence becomes a presence; the plinths speak by not speaking.

Simone’s refusal to debut rhymes with those removals: both are pauses that speak—not erasures, but absences demanding new language before anything returns to normal.

The back room and the street

In calmer years, a release plan is a release plan. The work is photographed, a checklist set, collectors warmed. This is not a calmer year. Chicago’s art machinery—museums, galleries, fair circuits—was already limping under COVID closures that began in March; by mid-month, major institutions, including the Art Institute of Chicago, had gone dark, with reopening dates slipping as the pandemic deepened. The whole system was improvising: appointments, private view links, “virtual” openings that looked like TV but felt like waiting rooms. Within that vacuum, the question of what not to do suddenly mattered as much as what to do.

Which is why Simone’s decision cut through. In the gallery offices, the objections were practical and predictable—sunk costs, promotion already in motion, a need for “solidarity” in the form of programming rather than silence. But causes aren’t spreadsheets; they’re systems of meaning, and meaning resists being monetized in real time without doing damage. The feathers you pluck today are the wings you can’t use tomorrow. Simone’s camp decided not to pluck.

The long view: this ground had already shifted

Here’s a fact we should not pretend is unrelated: Chicago’s gallery landscape was shifting before Floyd, before the boards, before the summer. In October 2019, the influential Shane Campbell Gallery stunned the scene by announcing it would close, an early contraction that set off months of “what next?” speculation even before the virus rewrote 2020. Go back further and the pattern is there: Rowley Kennerk Gallery closed in December 2010 after a formative five-year run; it’s the sort of disappearance that quietly changes what risks get taken—and by whom.

Why cite closures in a story about a single artist’s pause? Because ecosystems shape decisions. A city already dealing with lost venues, then a pandemic, then a protest summer, is a city in which withholding isn’t just a tactic; it’s a statement about governance—about who controls narrative, about who profits from it, and about when a name should not be used as a hedge against discomfort.

Capital, ethics, and the currency of timing

This is TheDollarHub, so let’s name the economics without pretending they’re separate from culture. In shocks, capital seeks cover: dollars firm, indices buckle and surge, institutions freeze then overcorrect. In art, the analog is private placement—quiet offers, off-calendar deals, fewer public comps. That shelter can be stewardship, or it can be opacity. Summer 2020 wants clear windows, not mirrored glass.

Simone isn’t making a liquidity play. Withholding a scheduled release is costly in obvious ways (no invoicing, no press cycle) and priceless in one: it reclaims authorship. It says the work will not be used to anesthetize a moment that is, properly, painful. That isn’t anti-market; it’s anti-cooption. Collectors with long memories understand this intuitively: objects carry the aura of their births, their lives, and the company they keep. An artist who asserts narrative control in a moment of civic grief is not reducing future demand; he’s defining the terms of future belonging.

“One of the first” to pull out—and why that matters

In our reporting this June, Simone is among the first artists tied to a major Chicago debut to halt a release explicitly “for the movement,” rather than for COVID logistics alone. The line from his side isn’t performative: no auctions, no marketing, no public dates, and—crucially—no framing of moral stance as commercial theater. You don’t have to agree with the move to see its coherence. It belongs to the same grammar Chicago is using on its streets and plinths: a deliberate absence that insists on a different conversation first. (If you want a proxy for how the city itself framed that conversation, look at the official language surrounding the statue removals and the municipal embrace of protest-board preservation—both cast as safety, process, and listening, not erasure.)

What gets saved—and who decides

From a conservation standpoint, 2020 is maddening. Plywood is not a museum material. Sun, rain, and scaffolding do their work. Yet by mid-summer, Chicago has seeded multiple efforts to document and preserve protest boards, with neighborhood exhibits and city-backed programs taking shape to keep the images—and the messages—alive after the glass returns. Simone’s pause belongs to the same impulse: rescue the meaning, even if it slows the market.

What happens next

No one truly knows. The gallery can push, Simone’s camp can refuse, and the summer can outlast them both. Or the parties can agree on a quieter path: no public dates, no framed-as-virtue press cycle, just a commitment to place—to match works with collectors who treat them as cultural responsibility more than portfolio position.

The city, too, will decide. Whether the boards become archives or compost depends on space, money, and will. Whether the pedestals remain empty or hold new forms depends on whether we can agree that some stories hurt when told in bronze. And whether artists can say not now without being punished by the mechanisms of their own careers depends on whether an industry built on timing can accept that, sometimes, timing is the message.

For now, Simone’s camp has said the only three words that feel honest in this heat: later, not now.

Research Notebook (for readers & reporters)

Shane Campbell Gallery closure (2019): Widely reported shutdown announced October 28, 2019—an early jolt to Chicago’s ecosystem before the pandemic.

Rowley Kennerk Gallery closure (2010): Confirmed December 2010 closure after a formative five-year run; an enduring reference point in conversations about risk and program depth.

Protest boards & preservation (2020): WBEZ reported on the rapid spread of plywood murals and the preservation question; city launched Boards of Change (July 29) to formalize the effort; neighborhood exhibits followed in the fall.

Columbus statues removed (July 24, 2020): City statement confirms temporary removals at Grant Park and Arrigo Park amid safety concerns; later debates over permanence continued.

COVID closures frame the calendar: Early March lists show Chicago cultural institutions—including the Art Institute of Chicago—shuttering or postponing, reshaping release strategies citywide.

Editor’s note: This dispatch is published as it would have been filed in June–July 2020 to preserve the texture and ethics of the moment. It is not investment advice; TheDollarHub covers culture where it crosses capital, and vice versa.