Holiday makers can hardly have failed to notice 2023 was a stellar year for the pound. Of the world’s major currencies, sterling was a top performer.

Every £100 taken abroad would have purchased almost $121 at the start of the year but buys just over $125 now. That is not a bad performance when the greenback has gained value against most global currencies this year.

For British travellers to the Continent, the exchange rate has improved from almost €113 to €116 and change.

Across the G10 currencies this year, only the Swiss franc performed better.

The pound’s strength has implications beyond just travel – it helps take the edge off inflation by reducing the sterling cost of goods and services bought from overseas.

Britain’s relatively resilient economy has helped, particularly when compared with the eurozone where Germany is mired in a seemingly endless cycle of recession and stagnation

Higher interest rates push up currencies by dragging more international cash into the country, with investors attracted by higher returns.

The Bank of England, European Central Bank and Federal Reserve have all raised borrowing costs more this year than financial markets anticipated back at the dawn of 2023.

But exchange rates are a relative game, and over the past year, the Bank of England has overshot interest rate expectations by more than the other central banks and is now expected to hold rates higher for longer.

At the other end of the spectrum, the Japanese yen and the Norwegian Krone vied to be the biggest fallers in the G10 currency league, both losing around 10pc against the US dollar.

Japan’s central bank has kept interest rates in negative territory. The Norwegian Government has been selling krone to buy foreign currency, while a drop in energy prices since last winter has hit exports.

Elsewhere in the world, much more dramatic slumps and booms have swept through the currency markets. Here are the biggest winners and losers of the past 12 months.

Winners

Afghan afghani

Afghanistan’s exchange rate story is one of remarkable recovery over the past year, taking the afghani to its highest level against the dollar since early 2018.

This year’s gain of more than 28pc came two years after the Taliban’s return to power in 2021. That sent the currency tumbling to its nadir in early 2022, as Kabul was cut off from international funds. But the afghani has more than recovered those losses.

The rebound is more than can be said for the wider economy – GDP crashed by 25pc after the Taliban takeover and the World Bank expects no growth this year. Life under the repressive regime is particularly harsh for women.

The currency has recovered in part because some aid flows have resumed. The authorities have also banned the use of foreign currencies, boosting local demand for the afghani.

But the World Bank has warned the exchange rate is distinctly vulnerable to any interruption in those flows of dollars.

Colombian peso

High interest rates are a key factor behind the peso’s near-22pc rise this year, as international investors put their cash into a country where the central bank’s base rate is 13.25pc.

Goldman Sachs expects the currency to be a strong performer in 2024 as well, as the central bank is prepared to battle inflation even if growth slows.

A fall in imports combined with a stronger tourism industry have also helped support the currency by trimming the country’s current account deficit, while foreign direct investment has kept on flowing.

Albanian lek

The Adriatic nation might have a poor reputation in Britain but its currency, the lek, is among the world’s strongest performers, climbing 13pc against the US dollar this year.

Albania has won praise from the IMF, as well as currency traders. The international watchdog’s latest review cheered on the country as “one of the stronger performers in the region” with “a strong rebound in tourism” and forecast-beating growth.

Bringing the public finances back into line and getting inflation under control has also helped, the IMF said, as it predicted “robust” economic growth of 3.6pc for 2023 and 3.3pc for 2024.

Losers

Angolan kwanza

Oil-producing Angola has been hit hard by both a drop in global prices this year and its own production problems. As a result, its currency dropped by more than 39pc against the dollar.

Sales of black gold are a key source of foreign currency in the country and the Angolian government prioritised the use of its scarce funds to repay foreign debts rather than to keep propping up the currency.

A member of OPEC, it has refused to join in with production cuts as it is keen to keep the vital revenue from oil sales flowing.

The result has been a jump in inflation, which has been exacerbated by a cut in subsidies. The kwanza is suffering as a result.

Nigerian naira

A currency devaluation in June sent inflation spiralling to more than 25pc in Nigeria, but the drop in official rates was not the end of the decline for the naira this year. Those changing money find that, in practice, the naira buys fewer dollars than indicated by the official rate.

The currency has lost almost 44pc against the dollar this year. The hope is that the lower exchange rate will allow investment and trade to improve.

Analysts at Citi suggest scrapping petrol subsidies and raising oil production would help improve the exchange rate.

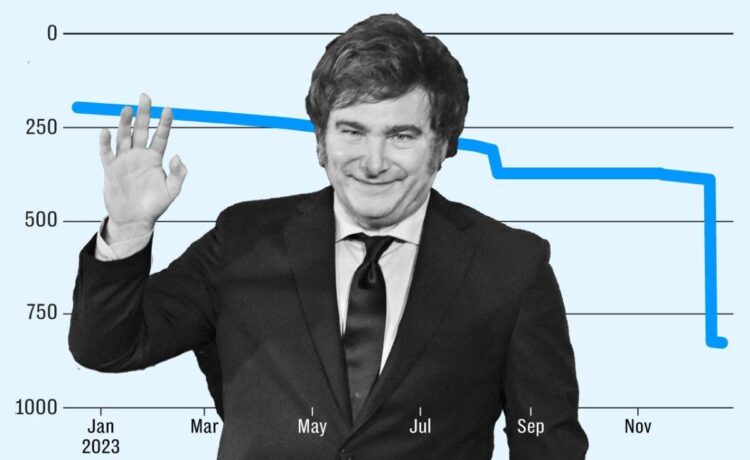

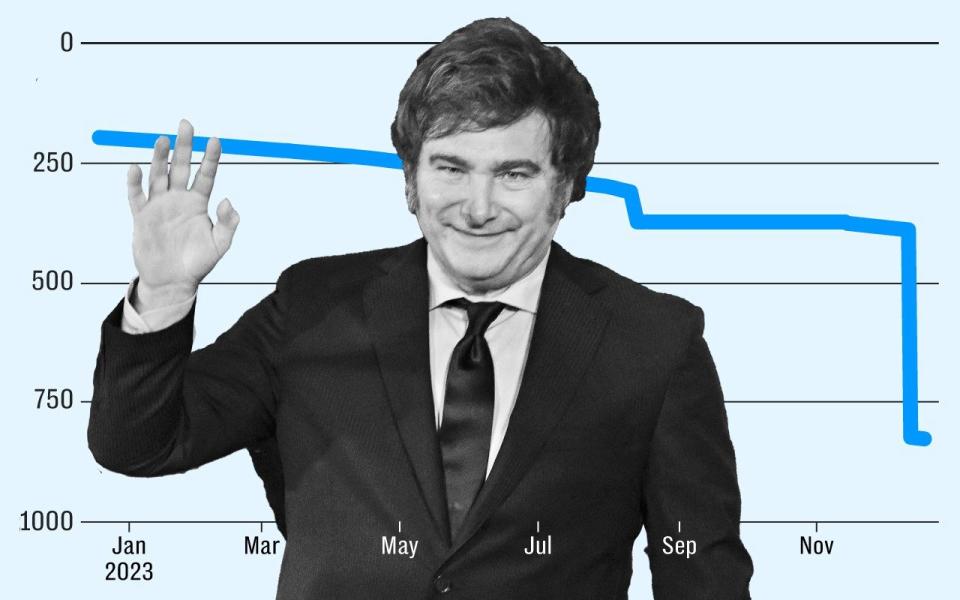

Argentine peso

Perennial crisis victim Argentina has not missed out on the action this year.

By the start of December, the peso had shed more than half of its value. Then Javier Milei, the new President, announced a further 54pc devaluation – taking the total loss to more than three quarters.

The devaluation is part of a programme of shock therapy that the wild-haired President hopes will get the stricken economy back onto an even keel.

Inflation is rampaging at more than 140pc but the devaluation will, at least initially, send it higher as the cost of imports rises.

Perhaps Milei’s most radical promise is to scrap the peso altogether. He has proposed adopting the dollar instead to try to bring some much-needed stability to the nation.

That would be one way to make sure the peso does not end up on this list again next year.

Lebanese lira

Bottom of the list of currency shame is Lebanon, an economy in the grip of a seemingly endless tragedy.

Lebanon’s government remains in default, having failed to pay an international debt for the first time in its history in March 2020.

The country has been without a president for more than a year, while the powerful Iran-backed Hezbollah militia has joined in with Hamas’ attacks on Israel, lobbing missiles over Lebanon’s southern border.

In February of this year, it devalued its official exchange rate by 90pc. The currency has barely moved since – it is still down 89.9pc against the US dollar over the year as a whole.

More pain is to come. Maya Senunssi at Oxford Economics says: “Prospects of any sustained recovery are bleak, absent a reform-oriented domestic leadership.”

Recommended

Why Javier Milei’s chainsaw economics won IMF’s approval when Trussonomics didn’t