BRAIN DRAIN

In recent years, the conversation around economic mobility and quality of life has intensified in South Asia, as white-collar professionals increasingly seek opportunities abroad.

This trend is not merely aspirational; it is a direct consequence of the widening gap in the real return on labour, which measures purchasing power after adjusting for inflation and cost of living, between South Asia and developed economies. Structural economic challenges, including runaway inflation, currency depreciation and stagnant wage growth, have eroded the financial stability of skilled workers, pushing them toward more lucrative markets.

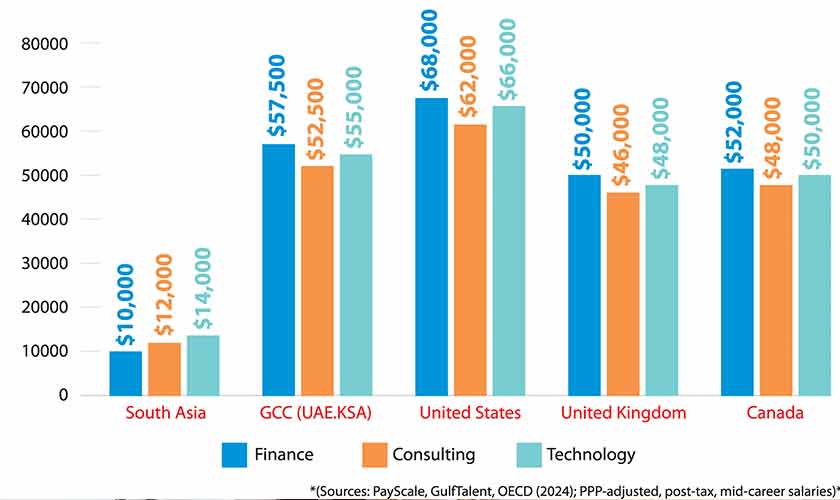

Economists use purchasing power parity (PPP), which adjusts post-tax salaries to compare compensation more accurately across countries. PPP adjusts for differences in price levels across countries, reflecting what a salary can actually buy in terms of goods and services within a local economy. For example, while a tech worker in San Francisco might earn $130,000, the PPP-adjusted figure might be closer to $66,000 due to high local taxes and living costs. Conversely, a similar worker in Riyadh earning $85,000 might have a PPP-adjusted salary close to $55,000, due to no income tax and subsidised services. These adjustments give a more accurate picture of economic well-being and cross-country comparability.

The wage stagnation crisis in South Asia is particularly evident in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, which collectively produce millions of engineers, finance professionals, and consultants annually. Despite this, real incomes have failed to keep pace with inflation. In Pakistan, urban inflation averaged 29.4 per cent in 2023 according to the State Bank of Pakistan, one of the highest rates globally.

A mid-level finance professional in Karachi or Lahore earns between $6,000 and $10,000 annually, but after adjusting for inflation, this salary is worth 30–40 per cent less than a decade ago, as reported by the World Bank in 2024. Despite rapid GDP growth in India, real wages for white-collar professionals grew at just 2.1 per cent annually between 2018 and 2023, far below inflation, according to the International Labour Organization.

In contrast, professionals in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), North America and Europe enjoy significantly higher purchasing power parity (PPP)-adjusted earnings, allowing for greater savings and investment. The disparity is stark when comparing salaries across regions. For instance, a finance professional in Dubai earns 5.75 times more than their counterpart in Pakistan after adjusting for living costs, while a tech worker in the US retains 4.7 times more purchasing power than one in India. Even after accounting for higher living expenses in Western cities, net disposable income is three to five times greater than in South Asia.

The given table provides a snapshot of approximate PPP-adjusted, post-tax annual salary levels in USD for mid-career professionals across five major regions:

Ultimately, South Asia’s professionals are not fleeing for luxury but for seeking basic financial security. Without urgent reforms, the region risks perpetual brain drain, stifling its economic potential.

Several structural and economic factors explain this gap. Developed economies invest heavily in automation, infrastructure, and research and development, leading to higher output per worker. For example, the US tech sector’s productivity growth of 3.2 per cent annually outpaces India’s 1.8 per cent, according to the OECD in 2023.

South Asia’s large informal economy, which accounts for 60 per cent of employment in Pakistan and 81 per cent in India, depresses formal wage growth, as noted by the ILO. Currency depreciation and inflation further exacerbate the problem. Pakistan’s rupee lost 50 per cent of its value against the US dollar since 2018, while India’s rupee has depreciated by 22 per cent, according to the IMF in 2024.

Inflation in South Asia, averaging 12 per cent, dwarfs Western rates, such as 3.9 per cent in the US and 4.2 per cent in the EU, further eroding real wages. Labour market dynamics also play a role. The GCC’s tax-free salaries and subsidised housing boost disposable income, and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 has increased expatriate salaries in tech and finance by 20 per cent since 2021, according to GulfTalent. In contrast, South Asian wages remain unindexed to inflation, with weak labour protections and stagnant pay scales.

The exodus of skilled workers has severe long-term consequences for South Asia. India incurs an estimated annual loss of $11 billion due to the emigration of skilled professionals, encompassing lost tax revenues and public investments in education. According to the Pakistan Medical and Dental Council, Pakistan’s healthcare sector faces a shortage of specialists due to migration. Bangladesh’s finance sector reports a high annual attrition rate to the Middle East, as highlighted by the Dhaka Tribune. This brain drain undermines local industries, reduces productivity, and perpetuates a cycle of low wages and poor economic outcomes.

To reverse this trend, South Asian governments must implement policies that stabilise currencies, control inflation and align salaries with global benchmarks. Monetary reforms, such as Pakistan’s central bank targeting single-digit inflation by 2026, are a step in the right direction. As India has done with its $600 billion reserve buffer, building dollar reserves can help mitigate currency volatility. Sector-specific interventions, such as India’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for the tech sector, could boost wages by linking export revenues to salaries.

Enhancing productivity through upskilling programmes and infrastructure investment is also critical. Vietnam’s IT training programme in 2022 increased wages by 34 per cent in three years, a model that could be replicated in India. Bangladesh’s Hi-Tech Parks initiative aims to increase the size of the tech sector in Bangladesh to $5 billion by 2025, leading to increasing salaries of the tech workers as well, demonstrating the potential of targeted investments.

Ultimately, South Asia’s professionals are not fleeing for luxury but for seeking basic financial security. Without urgent reforms, the region risks perpetual brain drain, stifling its economic potential. The solution lies in higher nominal wages and restoring real purchasing power. Until then, migration will remain the only rational choice for the region’s brightest minds.

The writer is an investment banker based in Riyadh, with eight years of experience across consulting, corporate finance, strategy and investments. LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mustafafahim/