3

By Takeo Hoshi, Professor of Economics, University of Tokyo

By Takeo Hoshi, Professor of Economics, University of Tokyo

At the meeting of the UN PRI (United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment) held in Tokyo in October, Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida declared:

Japan has more than 2,100 trillion yen, or $14 trillion, in household financial assets, most of which are owned as savings. I am pushing forward a policy package to channel these huge assets from savings into investments, which I believe will contribute to sustainable growth not only in Japan, but also on a global scale.

By shifting Japan’s household savings from low-return bank deposits to medium-return securities, such as stocks, bonds and investment trusts, households can prepare better for life after retirement. Those savings that flow into the securities market can be used to finance attempts to find solutions for various social issues that many countries in the world face, such as climate change, increasing natural disasters and aging populations. The financial industry, on the whole, would benefit as well because many banks suffer from too many deposits, with the Bank of Japan (BOJ) continuing to pay negative interest rates on some reserves. Banks and other financial companies can enjoy more revenues as households buy more investment trusts and other financial products.

“Savings to investments” is an important part of Prime Minister Kishida’s “new form of capitalism”, but this policy slogan is not new. As early as the mid-1990s, the Japanese government realized that various regulations in financial markets made households hold most of their financial assets in the form of cash and deposits. Encouraging the shift from savings to investments so that savers enjoyed higher returns to better prepare for retirement and more funds flowed to growth industries was an important goal of the Japanese version of the Big Bang. The Big Bang financial reform, announced in November 1996, was an attempt to transform the traditional bank-centered, heavily regulated Japanese financial system into one based on “free, fair, and global” markets.

The Big Bang reform included several measures to increase market options for savers. For example, the types of investment trusts (Japanese equivalent of mutual funds) that could be offered to retail investors were expanded. Financial institutions other than securities companies, most notably commercial banks, were allowed to sell investment-trust products. To facilitate small investors’ participation in the stock market, the minimum amount of investment in a stock was lowered. The transaction tax on securities was abolished. Unfair trades, such as insider trading and front-running, were explicitly banned. Finally, to increase competition among securities companies, the entry and exit barriers were lowered.

Most of the Big Bang financial reforms were implemented by the target date of 2001, but the government’s efforts to encourage the shift from savings to investments continued. Both the economic reforms of Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi immediately following the Big Bang and the more recent Abenomics economic reforms of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe listed “savings to investments” as slogans.

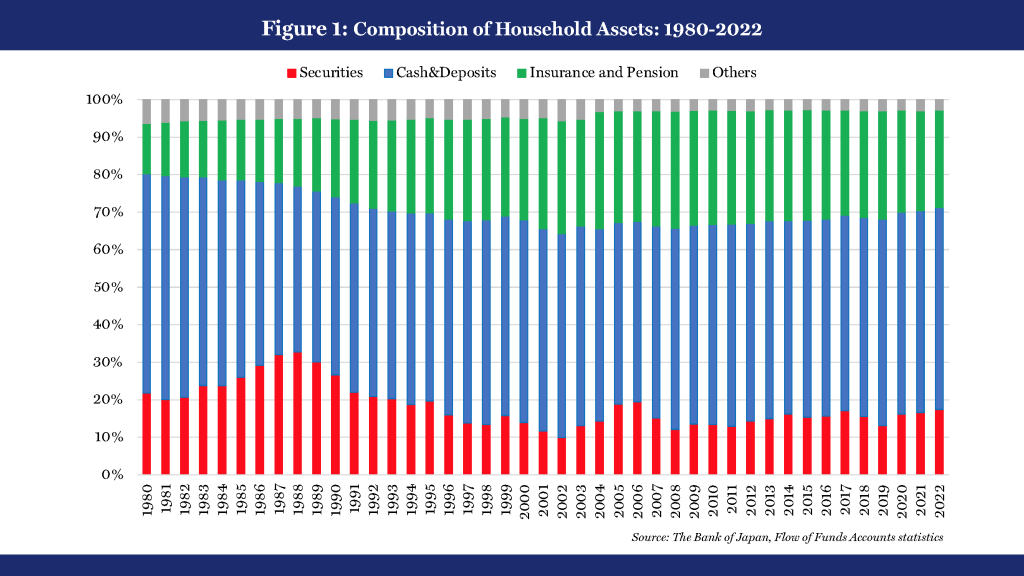

Despite the government’s promotions of “savings to investments” for more than two decades, the results to date do not look impressive. The shift of household financial assets from bank deposits to securities has not happened. The figure below shows the composition of Japanese households’ financial assets using the Flow of Funds Accounts statistics compiled by the Bank of Japan. During the late 1980s’ “bubble” period, Japanese households increased the proportion of financial assets held in the form of securities (stocks, bonds, and investment trusts) and reduced their dependence on cash and deposits. The trend, however, was quickly reversed as soon as the “bubble” burst. As late as the end of fiscal year 2022 (March 2023), the proportion of household financial assets held in the form of securities was less than 20 percent: well below the peak during the bubble years (more than 30 percent) and not much above the number when the Big Bang financial reform started in 1996 (16 percent).

Now, the Kishida administration is trying once again to shift Japanese household financial assets from savings to investments. Will the policy finally succeed? To answer this question, we must understand why Japanese households have been reluctant to invest more in financial products besides bank deposits and why the policies since the Big Bang have failed to change this attitude significantly.

Instead of trying to produce an exhaustive list of the reasons why Japanese households do not hold more stocks, bonds and investment trusts, I point out one important reason: the failure of financial investment products to generate attractive returns for retail customers.

Before the Big Bang, Japan’s investment trusts were found to underperform the benchmarks drastically. Part of this underperformance can be explained by a measurement bias introduced by a particular Japanese tax rule on open-type funds, but this bias alone cannot explain the underperformance. High asset turnover (churning), high commission fees and management incompetence have all been advanced as potential causes of the underperformance. Using data from the 1980s and 1990s, Takehara and Yamada (2003)1 found high asset turnover was the most important factor. Since many fund-management companies in Japan were (and still are) owned by securities companies, which can profit from more transactions, fund managers may have conflicts of interest concerning clients’ financial returns.

The Big Bang reform tried to remedy the situation by increasing competition in the financial-management industry. The number of fund-management companies, including new foreign entrants, increased. Takehara and Yamada found that fund underperformance and high asset turnover were less evident in the 1990s than in the 1980s. Nonetheless, the improvement appears to have failed to regain the trust of retail investors. As we saw in the figure above, Japanese households continued to hold most of their financial assets in cash and deposits in 2022.

Using more recent data, the Financial Services Agency, Japan (JFSA) (2020)2 reached the same conclusion: Japan’s retail investors do not trust domestic fund-management companies. The report argues:

The average performance of Japan’s publicly offered active investment trusts is not commensurate with the trust fees and other costs. Consequently, the asset management business has not gained enough confidence and support from customers, resulting in the sluggish growth in assets under management (AUM) of the publicly offered investment trust market. (See JFSA, Page 3)3

Will the Kishida administration finally achieve the shift from savings to investments? The core package of the relevant policy measures, the “Doubling Asset-based Income Plan”, specifies the following seven pillars:

- Expand NISA (Nippon Individual Savings Account): maximum investment increased, permanent tax-free treatment of returns, etc.;

- Improve the iDeCo (Individual-type Defined Contribution pension plan) system: raise the maximum age to start contributions, increase the maximum number of contributions, etc.;

- Create mechanisms to provide neutral and reliable advice to retail investors, such as MaPS (the Money and Pensions Service) in the United Kingdom;

- Expand corporations’ assistance in asset formation for their employees: tax incentives for corporations to encourage the employees to have NISA accounts, etc.;

- Enhance financial and economic education;

- Make Japan an international financial center;

- Promote the customer-oriented business operations of asset-management companies.

Looking through the list, Numbers 1, 2 and 4 attempt to increase the range of financial products and access to financial investments for households. They are extensions of the measures that have been tried since the Big Bang financial reforms by, for example, introducing more kinds of investment trusts and increasing the types of financial institutions allowed to sell them. Given their track records, these policies will not likely have large impacts by themselves.

Promoting the customer-oriented business operations of asset-management companies (Number 7) looks more promising. The JFSA recently called for more customer-oriented business operations in the general financial industry. For the asset-management business in particular, the JFSA has published a “progress report” identifying major issues and providing recommendations for improvement annually since 2020.

The latest JFSA report (2023)4 includes various useful recommendations for Japan’s asset-management companies based on comparative studies with the asset-management companies in the United States and Europe. For example, the report recommends Japan’s asset-management companies establish more independence from affiliated securities companies, improve disclosures on portfolio managers and holdings, and strengthen product governance. The report also finds that the net assets of most of the top investment trusts decline very quickly during the first year and a half after launch and calls for more responsible product origination in the interest of customers.

If the JFSA and Japan’s asset-management industry work together to establish “customer-oriented business operations”, they may succeed in gaining the trust of retail investors, and the financial assets of Japanese households may finally show a visible shift from cash and deposits to securities. The experience since the Big Bang financial reform, however, suggests that it will take much effort to gain the trust of retail investors, some of whom have experienced disappointing returns in the past. Unless the Japanese financial industry works harder than ever for customers’ interests, the goal of “savings to investments” will turn out to be elusive once again.

References

1 Hitoshi Takehara and Takeshi Yamada: “The Impact of Fund Turnover on Japanese Mutual Fund Performance,”Social Science Research Network (SSRN), November 18, 2003.

2 Financial Services Agency, Japan (JFSA): “Progress Report on Enhancing the Asset Management Business 2020,” June 2020.

3 Ibid.

4 Financial Services Agency, Japan (JFSA): “Progress Report 2023 For Enhancing Asset Management Business in Japan,” June 2023.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Takeo Hoshi is the Dean of the Graduate School of Economics at the University of Tokyo. Mr. Hoshi is also the Co-Chairman of the Academic Board of the Center for Industrial Development and Environmental Governance at Tsinghua University. His past academic appointments include faculty positions at Stanford University and the University of California, San Diego.