Log export dock, Vancouver Island, BC. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

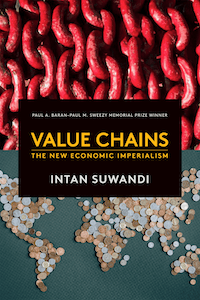

Intan Suwandi is an assistant professor of sociology and anthropology at Illinois State University and the author of Value Chains: The New Economic Imperialism (Monthly Review Press, 2019). I requested her views on how and why the world trading system helps the corporations in Europe, Japan and the U.S. (the ruling Triad of modern capitalism) and harms the Global South, an underreported viewpoint. That critique is the special focus of her book.

Seth Sandronsky: What are your thoughts on the driving force(s) of the Trump trade tariffs and the impacts on societies in the Global South?

Intan Suwandi: My answer to your question is quite general. I am not an economist who can give you a detailed analysis of this topic. As a matter of fact, Michael D. Yates just wrote a great commentary piece on MR Online earlier this month. But in general, my comment will be similar to other progressive/radical scholars (the ones who are not crossing to the other side, that is!).

SS: Understood.

IS: The Trump regime sees these tariffs as a way to rebalance trade; he claims that tariffs can encourage U.S. consumers to buy U.S. products, encourage U.S. manufacturing to come back home and bring back jobs, etc. Even mainstream economists, as you know, can tell you that, with how the global economy works, these claims are bogus. In terms of manufacturing itself, it is very unlikely that U.S. manufacturing will come back (considering how global commodity chains are organized, considering the infrastructure needs, the logic of capital accumulation, the history of stagnation, etc.). And as we know, tariffs are regressive; the way it is done now, it will only burden the working class and consumers.

SS: Can you share a snapshot of the history of tariffs?

IS: Historically, tariffs/protectionism were done to protect countries that were developing (to protect their industries via import substitution industrialization). In the Global South itself, developmentalism was attacked viciously by the Global North through many means, including the use of coups–because the latter did not want the Global South to develop and protect its industries.]

SS: What are your thoughts on tariffs and U.S. power globally?

IS: It is clear that Trump’s tariffs are about reinforcing/reasserting U.S. hegemonic, imperialist power in the global economy. It is about pressuring other countries to succumb to U.S. demands (otherwise, they will be punished). Under Trump, the U.S. does not hide its belief that other countries (especially the Global South) are supposed to be inferior compared to us. The imperialistic relations are highlighted. China is seen as an enemy (e.g., the New Cold War against China), and if countries fail to succumb to U.S. demands, they are seen as the enemies as well. (But obviously with the new 90-day tariff truce with China, Trump learned that he could not be stubborn after all.)

SS: In Value Chains, you provide a granular view of two Indonesian firms within the global trading system. How are current developments affecting commerce in that nation now?

IS: Indonesia was given a high tariff (32%, although with some commodities, like garments and textiles, the tariffs could in effect reach as high as 47%), with the trade deficit (ed. more U.S. imports than exports, for a trade deficit with Indonesia of $24.7 billion in 2024) as a reason. Soon enough, the Indonesian government learned that they had to negotiate. Some analyses I read have correctly  pointed out that their president, Prabowo Subianto (U.S.-trained, friendly to the West), did not want to lose his partnership with the U.S. Indonesia had been friendly with China under the previous president, Joko Widodo, although it had been keeping the U.S. close as well. Indonesia has also recently officially joined the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). China’s investments in the country are quite significant, especially in nickel production. I think the U.S. wants to warn Indonesia to make sure that it does not “pick the wrong side”–otherwise it would suffer the consequences, starting with trade.

pointed out that their president, Prabowo Subianto (U.S.-trained, friendly to the West), did not want to lose his partnership with the U.S. Indonesia had been friendly with China under the previous president, Joko Widodo, although it had been keeping the U.S. close as well. Indonesia has also recently officially joined the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). China’s investments in the country are quite significant, especially in nickel production. I think the U.S. wants to warn Indonesia to make sure that it does not “pick the wrong side”–otherwise it would suffer the consequences, starting with trade.

So what Indonesia did to lower the tariffs was to offer the U.S. many benefits. Some examples are as follows. First, promising the U.S. to increase imports of American commodities, including agricultural products (e.g., wheat, soybeans), petroleum gas, crude oil, and gasoline. This is very ironic–Indonesians consume U.S. soybeans now, and we have to increase our imports of American soybeans moving forward–exemplifying the lack of food sovereignty influenced by a long history of global food politics/agribusiness and structural adjustment policies, now enhanced by this negotiation. Second, the Indonesian government also offers U.S. multinationals that have been operating in Indonesia more incentives and benefits (e.g., in relation to lax regulations, etc.). Third, Indonesia offers opportunities in trade cooperation in relation to strategic/critical minerals that are deemed important for national defense.

SS: The New Cold War against China, with Democratic and Republican lawmakers’ support in Washington, DC, is gathering steam. How does that American militarism impact global trade?

IS: Global South countries are pressured to incorporate themselves more into the global exploitation scheme. This will enhance the imperialist relations, with the United States holding the hegemonic power (in the hope of defeating its rivals and enemies, especially China).

SS: What impact(s) do you see the BRICS nations bringing to the world system and the power of the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency?

IS: I think BRICS is an ambitious project, and if it is loyal to its goals, it can offer many things and challenge the Global North to a large extent. I am not sure if BRICS moves in the true spirit of the Third World Movement with its anti-imperialist background (the “Bandung Spirit”), but the South-South cooperation (anything from trade to the commitment to the de-dollarization movement) among its member countries–and these are nations with considerable resources of their own–can grow into an emerging “threat” to the Global North, enough that countries like the United States have been doing anything they can to prevent such a “multipolar” world from becoming stronger.

Indonesia’s joining BRICS in January 2025, was a great addition to the group. It is, first of all, symbolic, since Indonesia was one of the leaders of the Third World Movement (the Bandung Conference was held in Bandung, Indonesia, 70 years ago in 1955). Second, this is an allyship matter. Joining the BRICS nations can be seen as a test–whether Indonesia will continue to build economic and political partnership with China despite the U.S.-China New Cold War. A 2024 poll by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Studies Centre shows that there was a switch in the people’s preference in the ten ASEAN countries overall in terms of their ally choice (USA/China) compared to 2023, in which a slight majority chose China. But for several countries (including Indonesia, Malaysia and Laos), the numbers that chose China were more than 70% (see here). China is also the number one trading partner of Indonesia (see here).

Indonesia is also the largest producer of nickel (mainly a resource for the production of stainless steel) globally, and China is a significant investor. This relationship can be a test as to whether the South-South cooperation can work to a better end, or it will continue the usual problems brought about by industrialization. The Indonesian government has claimed that Chinese investment based on South-South cooperation will lead to technology transfers, among other benefits (see here.). But Indonesian researchers have pointed out the horrible problems that have infested the nickel mines (labor exploitation, environmental issues, land expropriation, etc.). Certainly, South-South cooperations are an important solution that we need to stop the North-South dependency, and BRICS can be a channel to make that happen. But obviously, none of this cooperation should mimic capitalist-imperialist relations (exploiter and the exploited) that we want to fight. Any solution should acknowledge and take seriously working-class (in its inclusive understanding) movements as a basis for creating what Marx himself calls “rich human beings.”